Transforming remote coastal communities

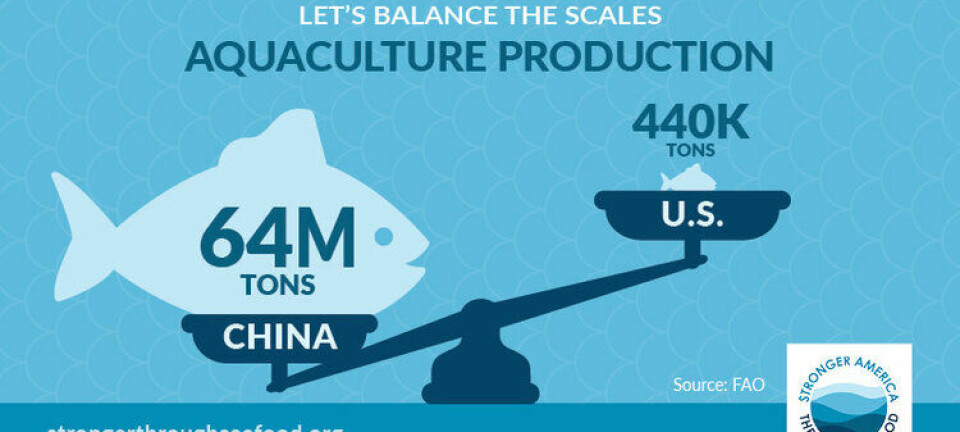

Mutually beneficial relationships between First Nations and the aquaculture industry in Canada include not only strengthening local and regional economies of First Nations, but have helped forge a resilient industry centered on the holistic traditional values of Canada’s first peoples.

Once home to a thriving commercial salmon industry and cannery, Klemtu, like many other coastal villages in BC, has seen little economic opportunity. In the mid 1980’s, the people of Klemtu decided to venture into aquaculture to stimulate their economy – they built their own salmon farm, and after several years, the business was very successful. However, in order to compete in the global market, a much larger scale of production was necessary. Thus in 1997, the Kitasoo/Xai'xais people met with MHC to discuss a partnership, and in 1998 this partnership was solidified with the signing of an agreement.

“It’s been great for our community”, said Les Neasloss with Kitasoo/Xai'xais First Nation. “I know that the world appetite for salmon is great – now that we are farming it and feeding that appetite with it, we are hoping we can keep the wild salmon.”

“Marine Harvest has really made a difference in our community and the lifestyles with our people”, said Neasloss.

Today, MHC and Kitasoo Seafoods, the local processing plant in Klemtu, jointly farm and process over 10 million pounds of salmon each year.

The people of Hope Island had a similar predicament – finding ways to provide economic opportunities in a rural coastal community.

In 2010, the Tlatlasikwala First Nation of Hope Island approached Marine Harvest Canada to inquire whether the Territory would be suitable for salmon aquaculture.

“We are always trying to explore ways and means of growth for our First Nation”, said Chief Tom Wallace of the Tlatlasikwala people. “The fish farming idea came to mind because it seemed like a lot of our neighboring First Nations were also thinking about it.”

Applications for two salmon farms were submitted by the Tlatlasikwala First Nation to regulating authorities in December 2013, and after thorough environmental review and public consultation process, two years later 600,000 Atlantic salmon smolts were transferred to Bull Harbour.

“I’m hoping that it’s an avenue for growth for my people as well as outside guests to our land. It’s exciting in the fact that there are doors that are available and could open”, said Wallace.

“We see this as part of a process that will hopefully entice some of our people to move back home. I’ve always had the dream that one day our people would repatriate”, said Wallace.

For the Tlowitsis First Nation of about 400 members, displacement from traditional territories in the 1960’s resulted in cultural and physical separation. Since then, the Nation has not had a residential community; however, by entering a collaborative partnership with Grieg Seafood BC, economic opportunities have been created that will assist them in developing new community lands on Vancouver Island.

“The Tlowitsis Nation’s partnership with Grieg Seafood is [also] integral to the Nation’s economic well-being”, said Chief John Smith of the Tlowitsis.

“Not only does it employ our members but Grieg Seafood has been supportive in many aspects of the Tlowitsis’ community. This partnership is vital to the Tlowitsis being able to be economically sustainable, especially as the reality of the new community is on the horizon.

Like many First Nations in BC the Tlowitsis are eager to develop a long lasting economy from our Traditional Territory. Clio Channel is a cornerstone for our Nation and it was after careful consideration, we developed an economic partnership with Grieg Seafood”, said Smith.

“Strong sustaining agreements with First Nations partners are those that reflect the Nations’ own community goals and provide tangible benefits,” said Marilyn Hutchinson of Grieg Seafood BC Ltd. “It takes many years and many meetings to build trust and share knowledge about each other before we enter into an agreement with a First Nation partner.”

Hutchinson added that an agreement-signing is not the end of years of meetings – it is just the beginning. Like any friendship and relationship, regular communication with the leaders, annual meetings with the entire community and inviting First Nations representatives to attend aquaculture events to stay abreast of ongoing changes in the industry, are a component of maintaining open dialogues.

A longer version of this article was published in the July issue of Fish Farming Expert.