Faster growth causing salmon deafness

Half of the world’s farmed salmon are part deaf due to accelerated growth rates in aquaculture, new research has found. The results now offer a better understanding of the effects of a common inner ear deformity, and some specific actions to tackle this welfare issue.

Published last week in the Journal of Experimental Biology, the research was led by a team at the University of Melbourne.

Last year the team showed that loss of hearing in farmed fish is caused by an inner ear deformity, and they have now linked that deformity to the fish’s fast growth rate.

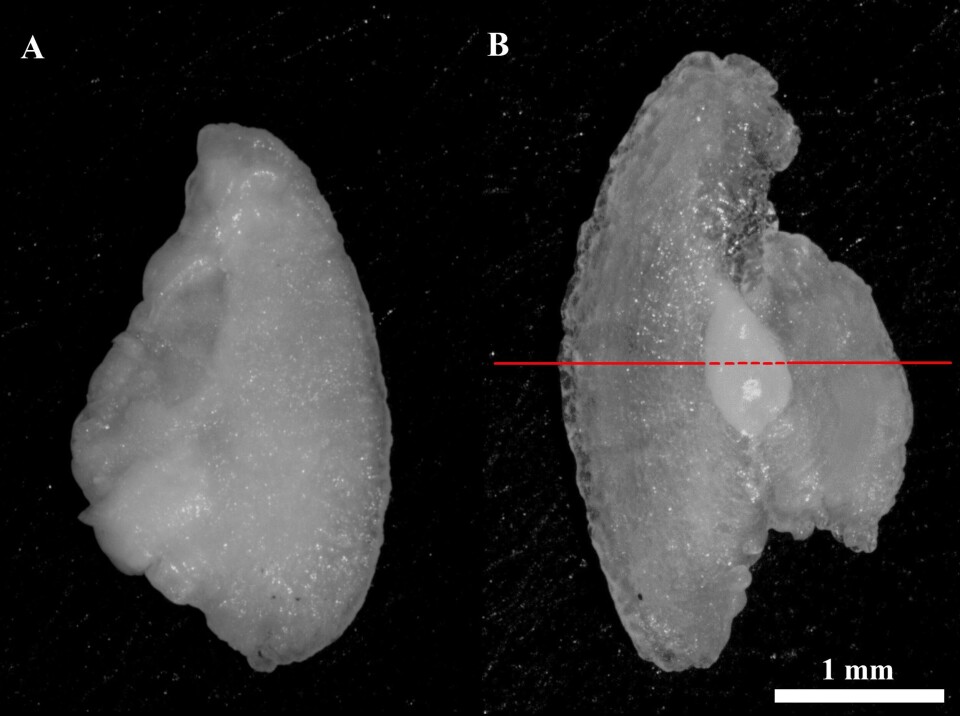

Otoliths are tiny crystals in a fish's inner ear which detect sound, much like the ear bones in humans, so even a small change can cause hearing problems.

The deformation was first recorded in the 1960s, but the team was the first to show that it affects more than 50 per cent of fully-grown hatchery-produced fish globally.

The cause of the otolith deformity was a 50-year mystery until now, said lead author Tormey Reimer from the School of Biosciences at the University of Melbourne.

“We looked at over 1,000 otoliths from fish farmed in Norway, Chile, Scotland, Canada and Australia, and found that this deformity was extremely common, but only in farmed fish,” Reimer said.

“Then we found that we could reduce the incidence of the deformity by reducing how fast a fish grew. The fastest-growing fish were three times more likely to be afflicted than the slowest, even at the same age. Such a clear result was unexpected.”

Gets worse with age

Normal otoliths are made of the mineral ‘aragonite’, but deformed otoliths are partly made of ‘vaterite’ which is lighter, larger, and less stable. The team showed that fish afflicted with vaterite could lose up to 50 per cent of their hearing.

Vaterite was seemingly caused by a combination of genetics, diet, and exposure to extended daylight, all of which differ between farmed and wild fish. But there was one factor that linked them all: growth rate.

Study co-author, Dr Tim Dempster, says that the deformity is irreversible, and its effects only get worse with age.

“These results raise questions about the welfare of farmed fish. In many countries, farming practices must allow for the ‘Five Freedoms’, which are freedom from hunger or thirst; freedom from discomfort; freedom from pain, injury or disease; freedom to express (most) normal behaviour; and freedom from fear and distress,” said Dempster from the University of Melbourne.

“Producing animals with deformities violates two of these freedoms: the freedom from disease, and the freedom to express normal behaviour. But fish farms are very noisy environments, so some hearing loss may reduce stress in hatcheries and sea cages. We still don’t know what this level of hearing loss means for production.”

Throwing money into the sea

The deformity could also explain why some conservation methods aren’t very effective. Due to many factors, wild salmon are declining in many areas. One strategy used to boost stocks is to release millions of farmed juveniles into spawning rivers.

“The next step should work out if vaterite affects the survival rate of hatchery fish released into the wild. Stocking rivers with hearing-impaired fish may be throwing money and resources into the sea,” said Dempster.

Reimer adds that since vaterite is irreversible once it’s begun, the key to control is prevention.

“Future research by the aquaculture industry may find ways to prevent the deformity without compromising growth rate,” she said.

“Our results provide hope of a solution. The close link with growth rate means that the prevalence of the earbone deformity is within the control of hatchery managers. Producing slower growing fish for release into the wild may increase their chances of survival in the long run.”

The full research article can be found here.