Farm or wild upbringing ‘doesn’t affect salmon goodness’

The nutritional content of a salmon is determined by what species it is, and not whether it is farmed or wild, new research in Canada has shown.

Analysis of several types of salmon was led by Stefanie Colombo, assistant professor of aquaculture at Dalhousie University’s Agriculture Campus, to shed light on a subject commonly misunderstood by consumers. Nutritional labelling is not required for salmon in Canada.

“I get a lot of questions from people I meet about farmed salmon and many people have the idea that it’s not good for you, that it's full of fat and contaminants,” Colombo told the university’s Dal News website.

Surprising results

“I knew these were misconceptions, but I wanted to know how it compared to the other types of salmon that were out there.”

“I was surprised by a few things,” added Colombo, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Aquaculture Nutrition.

“It’s really the species of salmon that makes the biggest difference in nutritional quality - not whether it was farm raised or wild caught, or whether it’s certified organic or environmentally certified. For example, there was a big difference in the wild salmon we looked at - between sockeye, chinook and Pacific.

“The results did clearly show that salmon types are different.”

Nutrient-dense

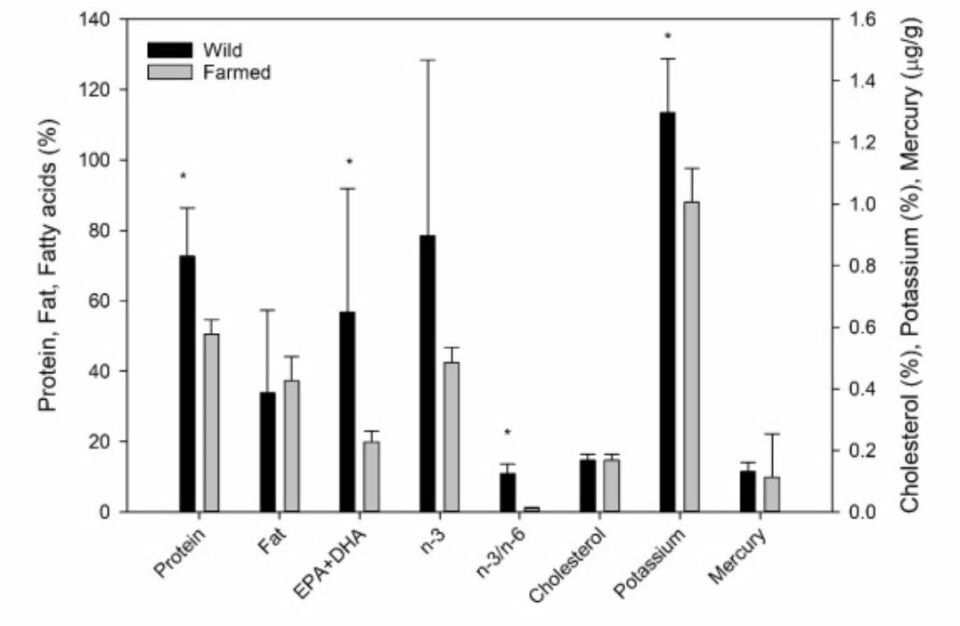

The study involved purchasing six different types of salmon that are commonly available to Canadian consumers to compare the nutritional information for each type, focusing in particular on the omega-3s. The fish included were farmed Atlantic, farmed organic Atlantic, farmed organic chinook, wild chinook, wild Pacific pink and wild sockeye.

The fish were analysed for various nutritional values, as well as for mercury. Colombo tested the different salmon species that were either wild, farmed, organic, non-organic, environmental certified, and non-environmental certified.

She found that the more expensive wild sockeye, which can be $31.50/lb, and wild chinook had the most nutrient-dense and highest omega-3 content of 81 mg/g and wild 79 mg/g respectively.

Affordable and available

But she also discovered that farmed Atlantic salmon, which had an omega-3 content of 20 mg/g and costs about $12.50/lb, had the lowest mercury content, had a high nutrient density, is more affordable and available on both of Canada’s coasts.

Wild Pacific (pink) salmon was found to be the least nutritionally dense due to high water content

“There’s actually no other study out there that has done this for Canadian salmon,” she says.

“There have been studies that focus on the contaminants, but they are several years old and things have changed in the environment and in aquaculture. So, it was an exciting opportunity to do an investigation.”

All salmon is good

Colombo’s analysis is detailed in the paper “Investigation of the nutritional composition of different types of salmon available to Canadian consumers”, published in the Journal of Agriculture and Food and available to read free here.

The scientist points out in the paper that although different types of salmon offer slightly different nutrient profiles, each type of salmon that was investigated offers health benefits for consumers, especially EPA and DHA.

Columbo also makes it clear that the study was not meant to be an exhaustive comparative analysis, as vitamins, minerals, carotenoids, etc., were not analysed. The aim was to provide a baseline for future research, since such a comparative baseline did not exist for salmon products available in Canada.