Salmon still ‘on brink’ in fish farm-free Washington state

Opponents of salmon farming in British Columbia expect a resurgence in wild salmon numbers if and when a government decision to close 19 net pen sites in the Discovery Islands is carried out. But that is not the experience just across the border in the US state of Washington, where net pen Atlantic salmon farming was banned in 2018.

A new report by the Washington State Recreation of Conservation Office has warned that some wild salmon populations are “on the brink of extinction” due to a variety of causes, although others have recovered that have nothing to do with fish farming. These include habitat degradation, harvest (fishing), climate change, fish passage barriers, hatcheries, and hydropower and dams.

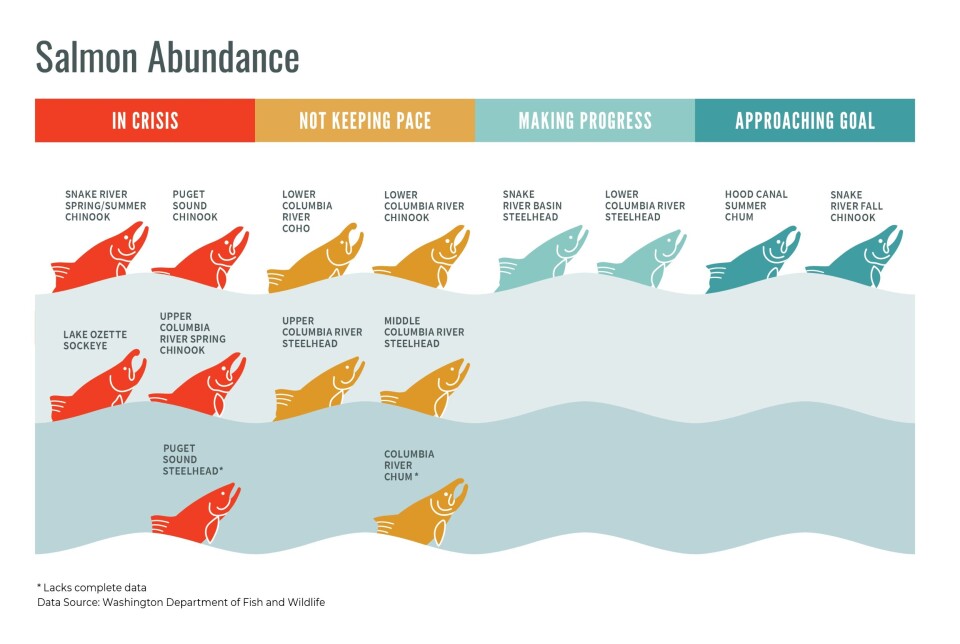

Some species, such as Hood Canal summer chum and Snake River fall Chinook, are moving in the right direction and are approaching their goals, while others, such as Puget Sound Chinook and upper Columbia River spring Chinook, continue to fall further behind and are in crisis.

Change or the fish die

The authors state: “Today, Washingtonians stand at a fork in the road with a clear choice: Continue with current practices and gradually lose salmon, orcas, and a way of life that has sustained the Pacific Northwest for eons. Or, change course and put Washington on a path to recovery that recognises salmon and other natural resources as vital to the state’s economy, growth, and prosperity.”

They add that “tough choices” will require Washingtonians to embrace their individual responsibilities and work together.

On the subject of habitat degradation, the report says that the state’s population is expected to grow to nine million by 2040, putting more pressure on habitat.

“Ensuring that salmon have places to grow, feed, and spawn will challenge land-use planners, local governments, businesses, and residents to rethink how Washington plans for salmon and how Washington accommodates more people on the landscape with less impact,” write the authors.

Toxic runoff

Stormwater running off roads in cities has become the top pollution source impacting water bodies in and around Puget Sound.

“As rain runs off impervious surfaces such as roofs, roads, and pavement, it collects pollution from oil, fertilisers, pesticides, garbage, and animal manure before heading, usually untreated, into street drains and then directly into streams and bays and then the ocean,” says the report.

“This soup of toxins in untreated stormwater can decrease the oxygen levels in the water, limit the ability of some salmon species to find food and avoid predators, and sometimes lead to large fish die-offs in urban streams.”

It adds that solutions to treat stormwater, such as running it through systems like rain gardens, have been found make the difference between life and death for salmon.

Water too warm

Climate change is another serious threat, melting glaciers which store much of the fresh water in the Pacific Northwest, meaning that they have less cold water to feed streams in the summer when the salmon need it most.

“Streams with temperatures greater than 64 degrees Fahrenheit (17.8°C) can stress salmon, and when rivers reach 70 degrees Fahrenheit (21°C), salmon begin to die. Without actions to address impacts from climate change there will be fewer salmon and fewer rivers where they can survive,” warns the report.

The authors say hatcheries are critical to rebuild salmon runs that have been reduced “to just a handful of fish” in some rivers and help reduce the impact of fishing on wild salmon.

“More than 80% of the salmon caught are born in hatcheries,” states the report. “Until habitat conditions improve, hatcheries are needed to meet tribal fishing and treaty obligations, support local and regional businesses reliant on fishing and outdoor recreation, and provide critical food for orcas, other wildlife, and humans.”

Weakening wild stocks

However, the report adds that hatchery programmes may hinder salmon recovery if they are not monitored, evaluated, and adaptively managed to limit risks to wild populations.

“Hatchery-raised fish can interbreed with wild salmon and weaken the fitness of wild stocks and they also can compete with wild salmon for food and other resources,” says the report.

“These factors contributed to salmon declines in the past, but wide recognition of these impacts has improved management of hatcheries statewide. Continued efforts to monitor, evaluate, and adaptively manage hatchery programs will ensure hatcheries can achieve their intended benefits without impeding recovery of wild salmon.”

More predators

The reports authors point to predation increased by a changing food web as another, complex problem.

“As humans have modified the land, they have upset the food webs and have made it more accommodating to predators and more hostile to salmon,” states the report.

“This is seen in two ways. First, native species (sea lions, cormorants) that eat salmon can benefit from a changing food web and grow in numbers.

Pikeminnows

“Scientists estimate that birds eat as much as 35% of the juvenile spring Chinook salmon in the upper Columbia River as the salmon head to the ocean. Northern pikeminnows also eat millions of young salmon and steelhead in the reservoirs behind dams on the Columbia and Snake Rivers.

“Second, a changing food web may benefit non-native, invading species. Northern pike, which is a non-native species introduced illegally, has established populations in eastern Washington. They are concerning because of their ability to eat large numbers of young salmon.

“Managing predators is a very real and complicated issue, confounded by scientific uncertainty and ethical issues. Consider sea lions, which are protected under federal law and have grown in large numbers under that protection. Now, they are eating endangered salmon by the tons. This issue is exacerbated by decreased habitat for salmon and potentially could nullify the ongoing work to recover salmon.

“How salmon, steelhead, and the habitats upon which they rely are managed must be addressed. Care must be taken not to upset this delicate balance.”

$3.7bn shortfall

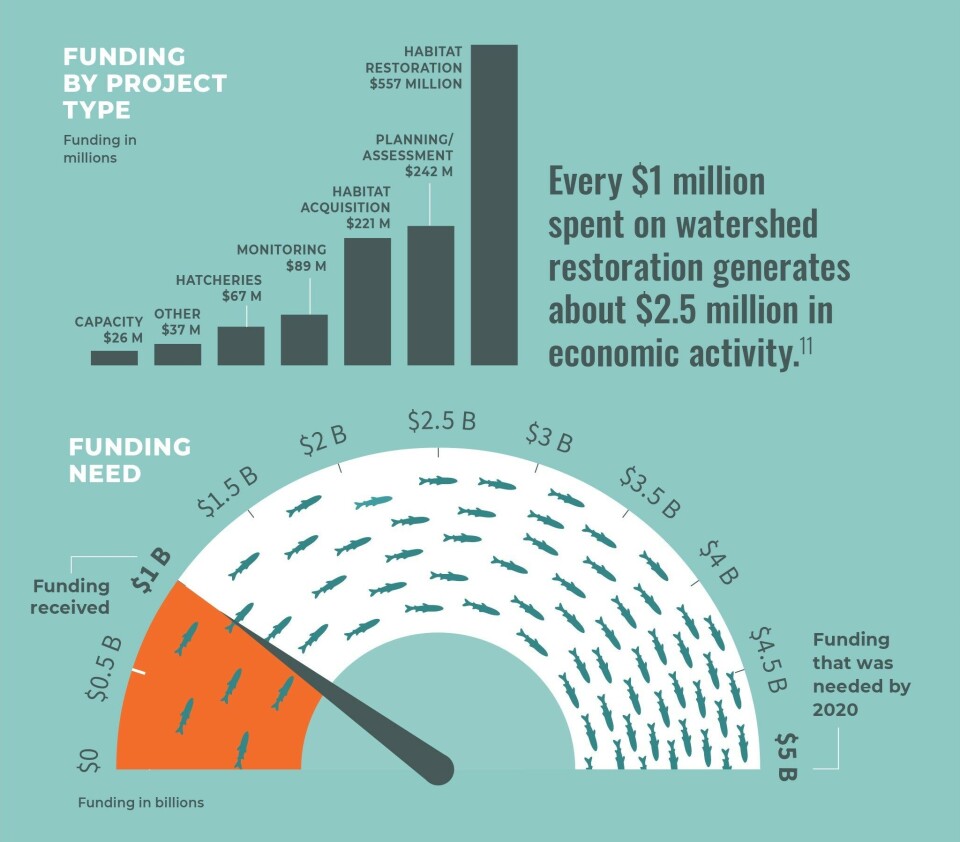

Funding for salmon recovery projects is another area that must be addressed, says the report.

“A 2011 study pegged the statewide cost of implementing habitat-related elements identified in regional salmon recovery plans for 2010-2019 at $4.7 billion in capital costs. As of today, only $1 bn has been invested or just under 22% of the need – a funding rate that will not achieve recovery,” warn the authors, who argue that every $1m spent on watershed restoration generates about $2.5m in economic activity.

Read the report, State of Salmon in Watersheds 2020, here.