Smolt producer chooses life in the slow lane

It's said good things come to those who wait, and that's something a Norwegian smolt producer hopes to prove.

From this year on, Sørsmolt has decided it will only produce so-called "old-smolts" grown slowly at a lower temperature for 15 months, rather than the more usual 12 months.

During the TEKSET conference in Trondheim, Ole Marius Farstad presented a future production plan for Sørsmolt and Fossing Storsmolt. He points out that he does not believe that optimal fish growth is achieved by going "full speed" from roe to set-out.

Regain lost growth

The company's hypothesis is based on the fact that fish that grow too much when young will slow down growth eventually. On the other hand, fish that grow slowly early will regain lost growth and compensate for this during their period in the sea.

“It lies in the genes, and it is determined early how fast the fish will grow later,” Farstad believes.

For example, he presents data over measured RGI (Relative Growth Index) from Trøndelag to Rogaland. For a zero-year smolt and a one-year smolt it is 93.6 and 95.3 respectively.

Natural temperatures

He then asks why growth is not better in the sea phase, when quality of both roe and feed have improved over the years. Farstad believes this may be due to the environmental issues and the solution for a better fish in the sea is to produce old-smolt, in natural temperatures.

"The harvested fish we produce spend 15 months in the fish farm, under low temperatures. They have a weight of about 100 grams when placed in the sea, and we achieve an RGI of 150 by five kilos of weight, after 11 months at sea,” he says.

10 months at sea

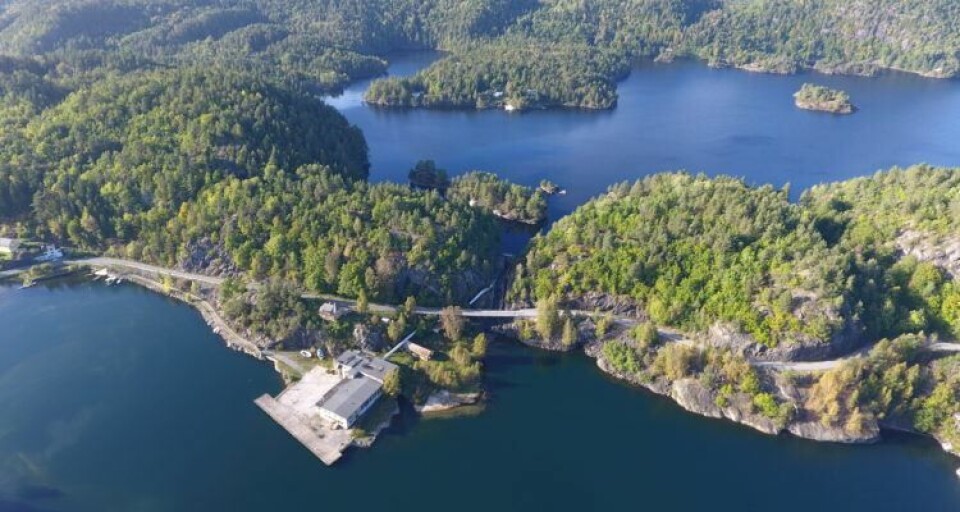

Until now, production of “old-smolt” in the south-east Norway town of Kragerø has only been done experimentally, but Farstad says that from 2018 the company will only produce “old-smolt” and 1½-year-olds. In addition, they are planning to produce smolt set out in spring time, which will have a weight of 200 grams at set-out.

"Here, we are testing the possibility to keep some of the smolt even longer in the facility. We keep some fish in the farms longer than 14 to 15 months, when they have an RGI of 125 to 135. These fish will be set out in spring time, with a weight of 200 grams and after 10 months in the sea, the fish has reached a weight of five kilograms," he said.

Old-smolts, old idea

Farstad also believes that by keeping the fish longer in the land-based facilities, they reduce the feed factor in the sea by as much as 10-20%, as the fish spend less time in the sea so less feed energy is utilised for swimming.

“The road ahead for us now is to document our findings further.”

But even with good and proven results, Farstad points out that the old-smolt is not a new discovery.

“In the late 80s and 90s, smolts were produced in 22 months. After set-out, they reached a weight of six kilos at New Year, after only eight months in the sea. Then they had an RGI of 147.”

More cells per centimetre

And the reason why smolts that grow up in cold surroundings grow better was documented over 74 years ago, he says. “In Ørretboka (The Trout Book), published in 1944, it is written that the number of cells is higher in fish that grow up in cold temperatures,” he quotes.

Farstad believes this is the reason why the texture of the fillet after slaughter remains fine even after rapid growth in the sea.

"This can come from just more cells per square centimetre," he says.