How chicken nudged salmon down the pecking order

US research concluding that chicken is more efficient than salmon at retaining protein for human consumption comes as no surprise to a Nofima scientist, who says the numbers are consistent with the Norwegian food institute’s findings.

"There is still room for improvements in salmon production, especially when it comes to utilising the entire salmon for human consumption," says Trine Ytrestøyl.

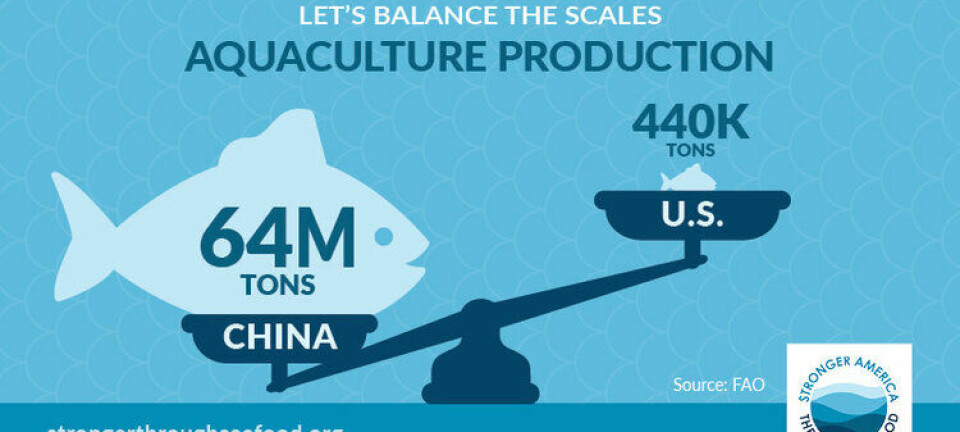

With the use of a new method of analysis, researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health's Center for a Liveable Future in Baltimore have found that chicken is the most effective animal for protein retention. Atlantic salmon is listed in second place, followed by rainbow trout, prawn and pig, without big differences between the species.

"There is still room for improvements in salmon production, especially when it comes to utilising the entire salmon for human consumption," says Trine Ytrestøyl.

With the use of a new method of analysis, researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health's Center for a Liveable Future in Baltimore have found that chicken is the most effective animal for protein retention. Atlantic salmon is listed in second place, followed by rainbow trout, prawn and pig, without big differences between the species.

The researchers estimate that about 27% of the protein and 25% of the calories in the feed for aquatic species are taken up and available in the final product for human consumption. For chicken, the analysis shows that approximately 37% of the protein and 27% of the calories are taken up and available to humans.

Similar results to previous study

Ytrestøyl said the US college’s review of resource utilisation was similar to what Nofima also did for Atlantic salmon a few years ago.

"They found similar numbers for retention of protein and energy in the edible part of the salmon that we found, so it seems to be in agreement for Atlanic salmon,” she added.

She pointed out that as she doesn’t have access to the data base for all the other species in the Johns Hopkins study, she can’t comment on whether the numbers used for protein / energy in feed and product, feed conversion ratio (FCR) and the proportion of the animal that goes to human consumption are representative of the different species.

"But for salmon, the numbers look OK, so I see no reason not to trust the figures they have found in the study (see Johns Hopkins video, below)," she said.

Ytrestøyl explained that what makes a big difference is the proportion of the product that is edible, and that is why the chicken is better than salmon in the American study.

“In figures calculated from a previous study (Bjørkli (2002)) salmon came out best because it was estimated that the edible proportion of the chicken was 50% and 68% in salmon, whereas from the United States it was estimated that an edible proportion of the chicken at 70-78% and for salmon 58-88%.”

She pointed out that the FCR for chicken and salmon is quite similar to chicken and salmon in completed studies (Bjørkli).

Ytrestøyl said the authors of the American article had not taken into account the weight of the mother animal when calculating retention of protein and energy.

“This has been done in previous research. The authors have also not taken into account mortality, wastage, and other losses, so they say in the discussion that they have probably overestimated retention values.”

Large variety within each species

In the study of salmon carried out by Nofima from 2012/2013 (Ytrestøyl et al., 2015), both lost / dead fish and wasted / lost feed have been taken into account, which means that it is estimated that economic retention of nutrients (how much feed is given to a crop from day one compared to how many tonnes of fish are harvested) and the potential for biological retention (the conversion rate for an individual fish) are significantly higher in salmon than stated in the study from 2015.

"What can be said is that there is a great variety within each species and it can indicate some uncertainty in the data material or that the variations in efficiency within each production cycle are high, both in terms of FCR and the share of the animal that goes for human consumption, something that gives great results in retention values.”

Lots of factors affecting FCR

If you test different values, using FCR at 1.15 and protein in feed of 35.5% (from Ytrestøyl et al 2015) you can see that the proportion for human consumption and FCR is more important for protein retention than the protein concentration in the feed, explains Ytrestøyl.

As an example, if one utilises 80% of the salmon, it will be at the level of chicken production in terms of protein retention.

"But a lot affects FCR, including mortality, feed loss, size at the time of slaughter, and feed composition.

“If the same share of the animal is used for human consumption (70%), the chicken will retain more protein than the salmon when it receives 21% protein in the feed, but less if the protein level in the chicken feed is increased to 23% or more. If the same share of the animal is used (70%) and the proportion of protein in the diet is 21% and 35.5%, the salmon must be down to an FCR of 1.0 to have better retention of protein than a chicken FCR of 1.7.”

These are only theoretical comparisons to illustrate the points in the article by the US researchers.

Will soon get new numbers on salmon

Ytrestøyl again emphasises that correct values for Norwegian chicken production with regard to FCR, and utilisation for human consumption are not known to her.

"Now we have numbers from 2013 for Norwegian salmon production, and soon new data will come from 2017. But chicken production is undoubtedly an effective way of producing animal protein if using more of the chicken for human consumption than usual.”

The same, she thinks, can be said about salmon.

"There is still room for improvements in salmon production, especially when it comes to utilising the entire salmon for human consumption.”