Brexit could aid GM cause

The decision to leave the EU could be beneficial to the GM camelina project headed up by Rothamsted Research in Hertfordshire.

So project leader Dr Johnathan Napier told Fish Farming Expert, during a visit to the UK’s oldest agriculture research facility this week.

“The result of the EU referendum represents an interesting wrinkle in all of this, as it means the UK will no longer fall under the EU’s GM regulations and it’s possible in the future that the GM approval process will be different in the UK,” he reflected.

Dr Napier is overseeing the project, which has led to the development and successful cultivation of a unique strain of the plant which can produce oils containing the same amount (25%) of the key long chain omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA as fish oil.

He has managed to successfully grow the new strain of camelina plants under both glasshouse and outdoor conditions while feed trials – in conjunction with the University of Stirling and Biomar – using oil from the plants have proved that it does indeed work as an ideal substitute for fish oil.

Potential for growth

Although the new strain has only been grown in small scale batches to date – enough to produce 6-7 litres needed for a feed trial – it is clear that, should regulatory approval be granted, whether in the UK or further afield, its potential to allow the global aquaculture industry to grow is immense.

“One hectare can produce the same quantities of EPA and DHA as ¾ tonne of fish oil,” Dr Napier explains, “so a million hectares could already match the amount of fish oil (around 700,000 tonnes) that’s currently used by the aquafeeds industry each year, although our goal is to add to, rather than replace, the current marine sources of fish oils”.

“While a million hectares may sound like a lot,” he continues, “when you think that the Canadians alone currently plant around 8-9 million hectares of canola [oil seed rape] each year, it’s not a huge amount.”

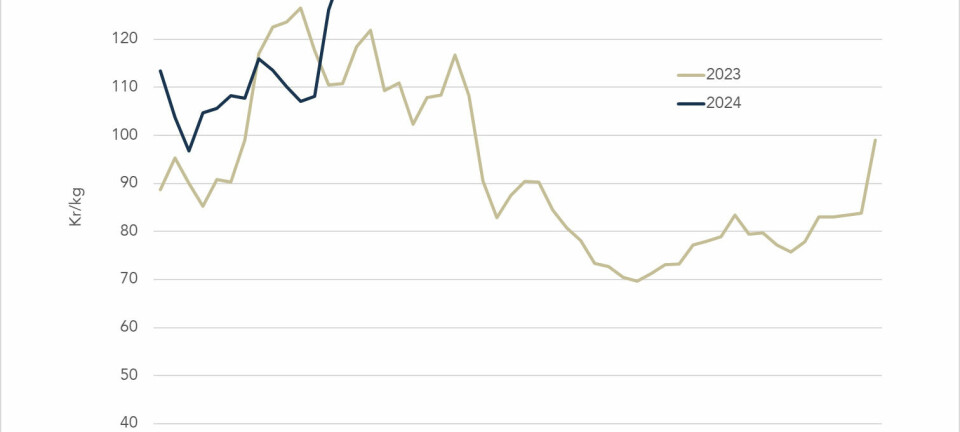

The price is right

What’s more, Dr Napier continues, if production is sufficiently up-scaled, oil from Rothamsted’s GM camelina should be considerably cheaper than fish oil to produce.

“Fish oil is currently traded at over $2000 dollars per tonne and if we compare that with the commodity price of vegetable oils at around $800/tonne, then we think that even a GM camelina oil will be highly competitive against fish oil.,” he reveals.

He also sees it as being much cheaper to produce than one other potential novel source of long chain fatty acids – algae.

“I went to a talk, at AE2016 in Edinburgh last month, about the project to produce algae for the aquaculture industry involving Bunge in Brazil,” he recalls, “and they told me that the cost of setting up the fermenters would be ‘north of $120 million’ which is a serious capital investment.”

“By contrast our camelina can be grown using existing agricultural land, machinery and processing technologies, while another advantage is that production can be scaled up or down quickly in line with demand – should the market for the oil suddenly drop, for example, farmers can switch to growing a different crop in the following production cycle.”

Political reality

Although Brexit could offer an opportunity in the medium term , Dr Napier expects that it’s more logical that GM camelina makes its commercial debut on the other side of the Atlantic, where attitudes to GM products are very different and the regulatory process much less prone to grinding to a halt for political reasons.

“We’re currently exploring the option of starting experimental trials in the US and, once these have started – subject to approval – the first batch of product should be commercially available to aquafeed producers in North America within 5 years,” he says.

While it might seem a shame for a UK-led project to bear fruit in a different continent first, any uptake should help to benefit the global salmon industry, as it could help ease up on the demand for fish oil – a resource that is likely to be one of the key limiting factors on the growth of salmon aquaculture in the coming years – as well as help allow the industry to grow without the need for the trend towards ever-decreasing levels of key O-3s in salmon products to continue.

Ultimately, however, benefits will also be returned to the UK, through protected intellectual property, while Dr Napier also hopes that the project will help to showcase “the world-class science and innovation – relevant to industry and consumers – which is being carried out here.”