Salmon health scare in Norway creating concern in Scotland

Siri Elise Dybdal siri@fishfarmingxpert.com

Salmon is well known for being a healthy food choice with high levels of Omega 3, which research has shown is beneficial for heart health and a range of diseases and conditions.

However, from time to time, negative claims about salmon do appear, and these can ‘take off’ with the help of sensationalist media coverage. An example of this is a case in 2004, where an American research report claimed that increased toxin levels in farm-raised salmon could pose health risks to people. The news quickly spread throughout international media, despite the fact that the report actually showed that individual contaminant concentrations in farmed or wild salmon did not exceed US Food and Drug Administration action or tolerance levels.

In recent months, there has also been high profile press coverage about salmon and various health risks. The main media frenzy has been in Norway, where media has been reporting how harmful chemicals find their way into salmon feed and pose a risk to human health. In the UK, the Norwegian media coverage on salmon and toxins has so far only caused some minor concern and has not been reported in the national press. But there has been negative attention in relations to salmon and other health issues, such as claims that omega 3 increases chances of prostate cancer as well as questions about the quality of smoked salmon and the ingredients in fish feed.

POPs causing concern It was a professor of medicine and a senior consultant at Haukeland University Hospital in Bergen, Norway, who raised the concern in Norwegian newspaper VG and claimed pregnant women, children and teenagers should limit their consumption of the fish. There was also a change in the official recommendations by the Norwegian Government so that it now emphasises that pregnant women should only eat two portions of salmon/oily fish per week.

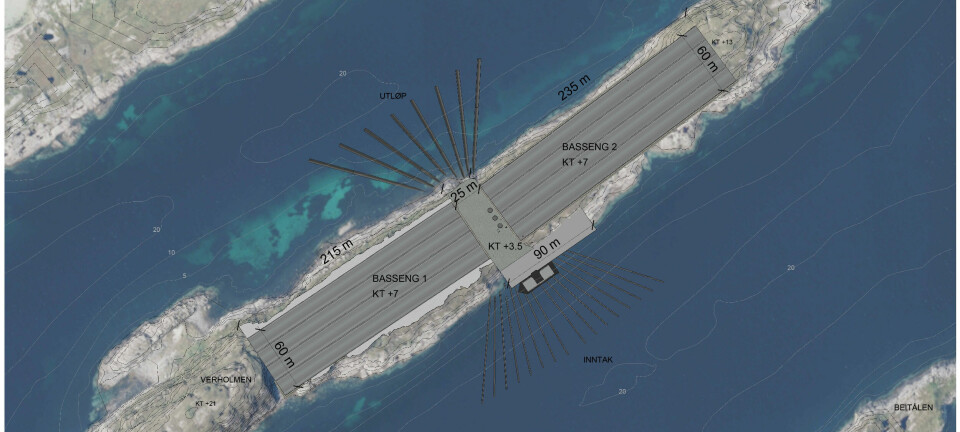

It was reported that some supermarkets threatened to ban salmon products from their shelves, as a result of the media revelations. And the supermarket chain ICA called for closed containment fish farms in order to prevent fish, diseases, sea lice or chemicals to leak out into the surrounding environment.

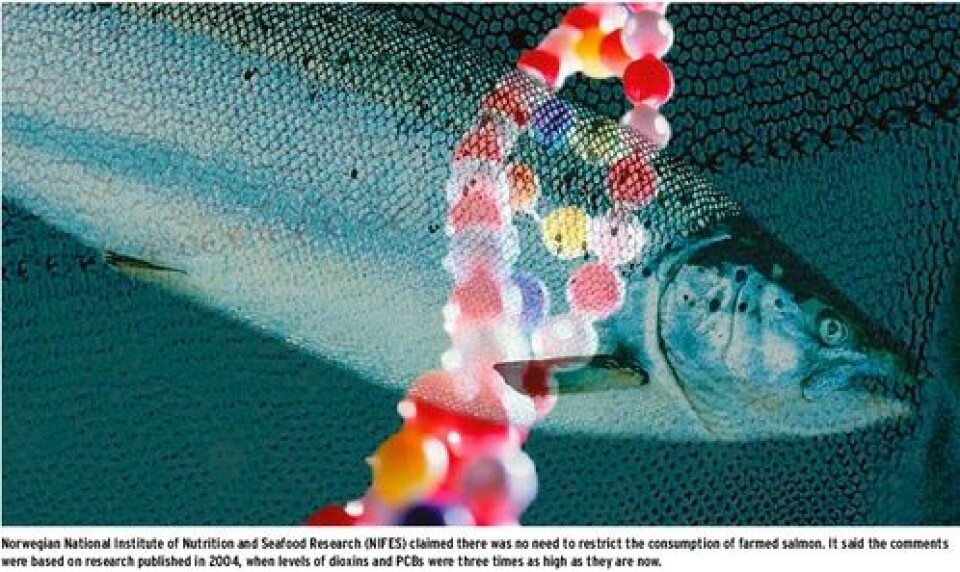

However, the Norwegian National Institute of Nutrition and Seafood Research (NIFES) claimed there was no need to restrict the consumption of farmed salmon. It said the comments were based on research published in 2004, when levels of dioxins and PCBs were three times as high as they are now.

The crux of the concern is POPs, a group of chemicals that resist degradation in nature, and accumulate in the environment for the long term. Many are known to pose a variety of significant health risks to humans including cancer.POPs are found in marine ecosystems, mostly as a result of industrial and agricultural run-off. They accumulate in, for example, the bodies of oily, high-fat fish such as blue whiting and capelin. Fish oil from these species is an important ingredient in feed pellets for farmed salmon. But when the feed is given to farmed salmon, the POPs are then passed on.

However, consumer demand has prompted a shift to vegetable oil in recent years, decreasing the level of fish oil –and subsequently POPs. This means that there is even a smaller impact today. Still, concern in Norway escalated and it was reported that local fishermen were worried that salmon farms are poisoning surrounding wild fish, which may be accumulating POPs by eating the pellets that fall through the salmon pens to the sea floor.

Conscious of the issue In the UK, the wide media coverage in Norway has got limited attention. However, Julie Edgar, spokesperson for the industry body Scottish Salmon Producers’ Organisation (SSPO) says the industry has been very aware of the situation: “We were obviously very conscious of the coverage in Norway this summer but it has not prompted much, if any, interest here in Scotland,” she says.

Edgar points out that in general, the health story for salmon is very strong: “Generally health claims, when corroborated by an official body like the European Joint Health Claims Initiative, can be very positive for food products. Scottish salmon has such a JCHI claim for heart health. The Omega 3 story for salmon is very strong, offering many different health benefits for all age groups. When there are so many health benefits to foods, like salmon, which are also tasty and easy to cook consumers have a complete package and are happy to purchase. “It can be a concern when negative health claims are made, but consumer reaction depends on how credible the source of the claim is perceived to be and how much consumers enjoy the product anyway,” she points out. Well within international safety limits Scottish anti-salmon farming lobby groups such as the Outer Hebrides Against Fish Farms (OHAFF), has picked up on the Norwegian media coverage. OHAFF claims the news is bound to raise concerns for women - “especially pregnant women over consumption of Norwegian farmed salmon that is widely available in high street supermarkets in the UK.”

In a statement, OHAFF’s spokesperson, Peter Urpeth, said: “This is not the first time that serious concerns have been raised about the safety of eating farmed salmon. The industry makes outlandish and contested claims about the super food value of its products, but these recent scientific surveys show that many specialists very much disagree with their claims. Most of the so-called ‘Scottish’ salmon industry is owned by Norwegian companies and, understandably, many consumers in the UK will be very concerned about the safety of this food, and we would always advise caution when consuming farmed foods the safety of which is very considerably questioned by such reports.”

However, in Britain, the amount of salmon that pregnant women are recommended to consume is already set to two portions – which is in line with the new advice from the Norwegian Government.

According to Health and Wellbeing, Public Health England: “Government recommendations are that adults and children should eat two portions of fish a week, including a portion of oily fish, as part of a healthy balanced diet. Oily fish include salmon, trout, mackerel, sardines and herring. An adult portion is based on a 140g serving.” “These recommendations are different for men and women. Women and girls who may become pregnant in the future, or who are pregnant or breastfeeding can eat up to two portions of oily fish a week. This is because pollutants found in oily fish may affect the development of a baby in the womb in the future. Women who won’t become pregnant in the future, men and boys can eat up to four portions of oily fish a week.”

Well within international safety limits David Sandison general manager of industry body Shetland Aquaculture emphasises that the UK has not changed its advice on salmon consumption and stresses that the levels of pollutants in Scottish salmon are well within safety limits used by both Britain and the EU.

He points out that pollutants are an issue that concerns the whole food industry: “This does not concern just salmon. It is a food issue full stop.”

He says the current argument in Norway is very similar to the issue that created international headlines 10 years ago, when the American study claimed farmed salmon was contaminated with toxic chemicals and should be eaten no more than three times a year.

Sandison recalls that the misleading study had a short term market effect on demand, but the Scottish industry put great resources into handling the accusations and eventually resolved the issue: “It was effectively dealt with. But it was hard thing to handle and we had to put in great resources to put the record straight,” he says and explains that misleading reporting by key news sources meant that incorrect news spread far afield. This made the job more challenging.

“But we clarified the situation,” he adds and points out that the conditions have only improved since then. According to Sandison, the occurrence of pollutants in the natural marine environment has actually reduced in the last decade, something which was also pointed out in the Norwegian debate: “There has been a reduction not only in the material potentially used in feed, but in the environment. It is driven from both ends,” he reveals and says he believes the issue should be of no concern to the industry and consumer due to the lack of evidence: “It’s a none-issue. It doesn’t concern the industry and it doesn’t concern the consumers.”

Linked to prostate cancer Another salmon health scare that got press coverage in the UK this summer was a report that claimed taking omega-3 supplements may increase the risk of aggressive prostate cancer by 70%. It also said the supplements were associated with a 44 per cent greater chance of developing low-grade prostate cancer.

In an interview with the Daily Mail, Dr Alan Kristal senior author of the paper, published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, said the levels of omega-3 linked to the increased cancer risk would be reached by taking just one supplement a day, or three or four meals of fish such as salmon and mackerel each week.

“There are good things in fish, so the message is moderation. It is probably not bad for you, and it tastes good,” he did add.

However, the sensationalist claims did not mean that Dr Iain Frame, Director of Research at Prostate Cancer UK would encourage people to change their diet: “Omega 3, such as is found in oily fish, has been the focus of a large amount of research in recent years, the majority of which points to it having wide ranging health benefits when eaten as part of a balanced diet. “Therefore we would not encourage any man to change their diet as a result of this study, but to speak to their doctor if they have any concerns about prostate cancer,” he was quoted in the Telegraph. In another newspaper report, also in the Daily Mail, the headline asked if there was something fishy about your smoked salmon. It criticised “the loophole in country of origin rules - salmon farmed in Norway but smoked in Scotland can be listed as Scottish salmon,” as well as the way salmon is smoked and cured. However, the journalist then went on to test which smoked salmon products on the market were best.

Not hit the consumer press Karen Galloway, market planning and strategy manager for Seafish Industry Authority, also says they have not been aware of any stories of salmon and toxins hitting the consumer news this summer: “Nobody here is aware of this,” she states.

Galloway claims that it will depend on the content of the story whether such news will have a damaging impact on demand. “It depends on the story. Consumers are not daft. They will have a degree of caution when it comes to the main street press. They know media make scare stories. Bad stories sell papers!” she points out.

However, it is when the story “runs and runs” it may be necessary to take action. “It is most likely to have an effect on of 1-2 weeks to a month. We are creatures of habit, we cook the same things, we buy what the children like. Unless there is a 100 per cent chance of cancer, we are not likely to change,” she claims. If the advice is not consistent, and scientists are saying different things she believes we tend to ignore it. “We think that they don’t know what they are talking about. “But if it is consistent and we hear the same thing again and again it is more likely to have an impact,” she adds.

This was the case with the horse meat scandal. “The horse meat scandal came at a relatively quiet time and reached the front pages again and again.” This she says was due to new cases and new research: “This was like oxygen to the fire.”

When the horse meat scandal hit, Galloway says consumers said what worried them the most was that they were being ripped off. They were wondering what was going on – “they were being told one thing on the packaging, and then something else.”

She says health scare stories could potentially sometimes have an impact long term: “It is the longer term impact that is concerning.”

She says headlines concerning what pregnant women should and shouldn’t eat do have a tendency to put the fear into people. “During pregnancy we are more aware of the ‘don’t eats’ than the majority of people. What would worry me is if they believe it then, they are more likely to retain this. “But most women know fish is good for us, but there will always be some who buy it. It is a complex issue,” she underlines.